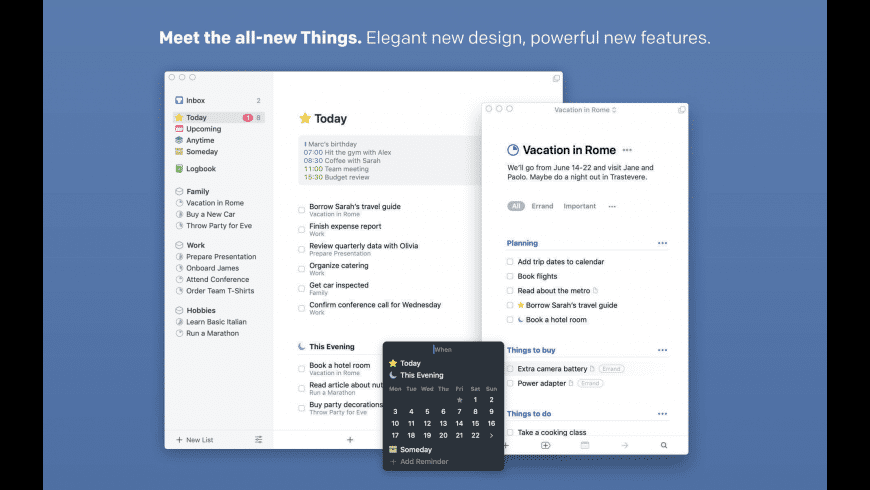

- Things 3 2 1 – Elegant Personal Task Management Software

- Things 3 2 1 – Elegant Personal Task Management System

- Things 3 2 1 – Elegant Personal Task Management Tool

Get 10% off of your first domain purchase at Hover: Huge thanks to Hover for sponsoring this video! So you want to graduate. Quadrant 2 comprises of things that are not urgent right now but important. Things like strategic planning, relationship building, exercise, preparation, education and other personal development activities – all things we know we need to do but somehow seldom get around to actually doing, because they don't feel urgent.

Wednesday, March 5, 2014

There's Springpad. There's Evernote. There's Google Tasks and TeuxDeux. There's a ton of personal task management software to choose from out there – perhaps hundreds, if not thousands – and depending on whom you're asking, one is significantly better than the other. But 'personal' being the operative word, one is inclined to ask, what does a personal task management software have to do with team-based tasks and enterprise-wide projects?

Task automation, working with teams and your personal task management tool

Task automation

Automation is a tricky, if not sensitive, subject. Whenever automation is broached, many people think of robots displacing human beings, of jobs disappearing, of tax collections diminishing, of the economy collapsing. This belief, of course, isn't unfounded, particularly when you think about Detroit and car manufacturing automation being a contributor to the city's decline.

And yet without task automation, the chance of the modern-day worker having difficulty surviving one fine day at the office increases, where one fine day means having to juggle multiple tasks and assignments, needing to determine which is urgent from which is not based on the metrics the company utilizes, responding to requests from other project managers or departments, and perhaps worst of all, having to look at the monster that is your ever-growing to-do list.

Overwhelm, as they say, can effectively kill motivation, and employee demotivation is the last thing a team leader wants to deal with when working with tight deadlines. This is where a team collaboration software that also functions as a personal task management tool can help save the day.

Working with teams

When working with teams, what team-based task management tools normally do is streamline the task execution process from start to finish. When a team member successfully completes an assigned task, the task management engine sends out an auto-notification to the next person in the task chain. When a task is about to go overdue, the auto-notification system kicks into gear again, ensuring that every task is done properly and on time.

Comindware Tracker and personal task management

While collaboration is the force behind Comindware Tracker, the software also functions as a personal task management tool. When tasks are assigned to you, they become your responsibility, and this is where things get personal.

When you login to Comindware Tracker, all of your tasks appear in your main dashboard, along with vital information such as due date, level of priority, task status, and others. This way, right at the start of the work day, you already have an idea which tasks to tackle first and, quite possibly, how your entire day will shape up.

Aside from those assigned to you, you can also create your own tasks, such as a list of things you've done for the day, week, month, or quarter so that when it's time to create a report, you won't have to look through various emails, files or reporting platforms, essentially saving you tons of time for other tasks – personal task management at its best.

Conclusion

Trust and accountability are essential for teamwork to really work. Every member comprising a team has something to contribute, but until personal responsibility is seriously internalized, successful team execution may still be far ahead. That being the case, a collaboration application that supports personal task management in a flexible and user-friendly way becomes a vital tool in your team's task management arsenal.

PART II: THE FIVE TASKS OF STRATEGIC

MANAGEMENT

The strategy-making, strategy-implementing process consists of five inter-

related managerial tasks:

1. Deciding what business the company will be in and forming a strategic vision

of where the organization needs to be headed - in effect, setting the

organization with a sense of purpose, providing long-term direction, and

establishing a clear mission to be achieved.

2. Converting the strategic vision and mission into measurable objectives and

performance targets.

3. Crafting a strategy to achieve the desired results.

4. Implementing and executing the chosen strategy efficiently and effectively.

5. Evaluating performance, reviewing new developments, and initiating corrective

adjustments in long-term direction, objectives, strategy, or implementation in

the light of actual experience, changing conditions, new ideas, and new

opportunities.

Figure 1-1 illustrates this process. Together, these five components define what

I mean by the term strategic management. Let's explore this framework in more

detail to set the stage for all that follows.

1. Developing a Strategic Vision and Business Mission

The foremost direction-the very first question that senior managers need to ask

is 'What is our vision for the company—what are we trying to do and to become?

' Developing a carefully reasoned answer to this question pushes managers to

consider what the company's business character is and should be and to develop a

clear picture of where the company needs to be headed over the next 5 to 10

years. Management's answer to 'who we are, what we do, and where we're headed'

shapes a course for the organization to take and helps establish a strong

organizational identity. What a company seeks to do and to become is commonly

termed the company's mission. A mission statement defines a company's

business and provides a clear view of what the company is trying to

accomplish for its customers. But managers also have to think strategically

about where they are trying to take the company. Management's concept of the

business needs to be supplemented with a concept of the company's future

business characteristic and long-term direction. Management's view of the kind

of company it is trying to create and its intent to be in a particular business

position represent a strategic vision for the company. By developing and

communicating a business mission and strategic vision, management educate the

workforce with a sense of purpose and a persuasive reasons for the company's

future direction. Here are some examples of company mission and vision

statements:

Examples of Company Mission and Vision Statements

Avis Rent-a-Car:

'Our business is renting cars. Our mission is total customer satisfaction.'

Public Service Company of New Mexico:

'Our mission is to work for the success of people we serve by providing our

customers reliable electric service, energy information, and energy options that

best satisfy their needs.'

American Red Cross:

'The mission of the American Red Cross is to improve the quality of human

life; to enhance self-reliance and concern for others; and to help people avoid,

prepare for, and cope with emergencies.'

Compaq Computer:

'To be the leading supplier of PCs and PC servers in all customer segments.'

2. Setting Objectives

The purpose of setting objectives is to convert managerial statements of business

mission and company direction into specific performance targets, something the

organization's progress can be measured by. Objective-setting implies challenge,

establishing performance targets that require stretch and disciplined effort. The

challenge of trying to close the gap between actual and desired performance

pushes an organization to be more inventive, to exhibit some urgency in

improving both its financial performance and its business position, and to be

more intentional and focused on its actions. Setting objectives that are

challenging but achievable can help guard against self-satisfied, non-directed and

internal confusion over what to accomplish. As Mitchell Leibovitz, CEO of Pep

Boys—Manny, Moe, and Jack, puts it, 'If you want to have ho-hum results, have

ho-hum objectives.'

The objectives managers establish should ideally include both short-term and

long-term performance targets. Short-term objectives spell out the immediate

improvements and outcomes management desires. Long-term objectives prompt

managers to now to position the company to perform well over the longer term.

As a rule, when alternative have to be made between achieving long-run

objectives and achieving short-run objectives, long-run objectives should take the

priority. Rarely does a company prosper from repeated management actions that

sacrifice better long-run performance for better short-term performance.

Objective-setting is required of all managers. Every unit in a company needs

concrete, measurable performance targets that contribute meaningfully toward

achieving company objectives. When company's general objectives are broken

down into specific targets for each organizational unit and lower-level managers

are responsible for achieving them, a results-oriented climate builds throughout

the enterprise. The ideal situation is a team effort where each organizational unit

is striving hard to produce results in its area of responsibility that will help the

company reach its performance targets and achieve its strategic vision.

From company general objectives, two types of performance objectives are

called for: financial objectives and strategic objectives. Financial objectives are

important because without acceptable financial performance an organization risks

being denied the resources it needs to grow and prosper. Strategic objectives are

needed to prompt managerial efforts to strengthen a company's overall business

and competitive position. Financial objectives typically relate to such measures

as earnings growth, return on investment, borrowing power, cash flow, and

shareholder returns. Strategic objectives, however, concern a company's

competitiveness and long-term business position in its markets: growing faster

than the industry average, overtaking key competitors on product quality or

customer service or market share, achieving lower overall costs than rivals,

boosting the company's reputation with customers, winning a stronger foothold

in international markets, exercising technological leadership, gaining a

sustainable competitive advantage, and capturing attractive growth opportunities.

Strategic objectives serve notice that management not only intends to deliver

good financial performance but also to improve the organization's competitive

strength and long-range business prospects. And here are examples of strategic

and financial objectives

Strategic and Financial Objectives of Well-Known Corporations

Apple Computer

'To offer the best possible personal computer technology, and to put that

technology in the hands of as many people as possible.'

Atlas Corporation

'To become a low-cost, medium-size gold producer, producing in excess of

125,000 ounces of gold a year and building gold reserves of 1,500,000 ounces.'

Exxon

To provide shareholders a secure investment with a superior return.'

3. Crafting a Strategy

Strategy-making brings into play the critical managerial issue of how to achieve

the targeted results in light of the organization's situation and prospects.

Objectives are the 'ends,' and strategy is the 'means' of achieving them. In effect,

strategy is the pattern of actions managers employ to achieve strategic and

financial performance targets. The task of crafting a strategy starts with solid

analyses of the company's internal and external situation. Only when armed

with hard analysis of the big picture are managers prepared to make a sound

strategy to achieve targeted strategic and financial results. Why?- Because

misanalysis of the situation greatly raises the risk of pursuing ill-awarded

strategic actions.

A company's strategy is typically a combination of (1) deliberate and purposeful

actions and (2) as-needed reactions to unanticipated developments and fresh

competitive pressures. As illustrated in Figure 1-2, strategy is more than what

managers have carefully set it out in advance and intend to do as part of some

important strategic plan. New circumstances always emerge, whether important

technological developments, rivals' successful new product introductions, newly

enacted government regulations and policies, widening consumer interest in

different kinds of performance features, or whatever. There's always enough

uncertainty about the future that managers cannot plan every strategic action in

advance and pursue their intended strategy without alteration. Company strategies

end up, therefore, being a composite of planned actions (intended strategy) and

as-needed reactions to unforeseen conditions ('unplanned' strategy responses).

Consequently, strategy is best considered as a combination of planned actions

and on-the-spot adaptive reactions to fresh developing industry and competitive

events. The strategy-making task involves developing a game plan, or intended

strategy, and then adapting it as events occur. A company's actual strategy is

something managers must craft as events arise outside and inside the company.

3.1. Strategy and Entrepreneurship

Crafting strategy is an exercise in entrepreneurship and outside-in strategic

thinking. The challenge is for company managers to keep their strategies closely

matched to such outside drivers as changing buyer preferences, the latest actions

of rivals, market opportunities and threats, and newly appearing business

conditions. Company strategies can't be responsive to changes in the business

environment unless managers exhibit entrepreneurship in studying market trends,

listening to customers, enhancing the company's competitiveness, and leading

company activities in new directions in a timely manner. Good strategy-making

is therefore inseparable from good business entrepreneurship. One cannot

exist without the other.

A company encounters two dangers when its managers fail to exercise strategy-

making entrepreneurship. One is a stale strategy. The faster a company's

business environment is changing, the more critical it becomes for its managers

to be good entrepreneurs in diagnosing shifting conditions and making strategic

adjustments. Coasting along with a set strategy tends to be riskier than making

modifications. Strategies that are increasingly not linked with market realities

make a company a good candidate for a performance crisis.

The second danger is inside-oriented strategic thinking. Managers with weak

entrepreneurial skills are usually risk-avoiding and hesitant to carry out a new

strategic course so long as the present strategy produces acceptable results.

They pay only neglectful attention to market trends and listen to customers

infrequently. Often, they either dismiss new outside developments as

unimportant ('we don't think it will really affect us') or else study them to death

before taking actions. Being comfortable with the present strategy, they focus

their energy and attention inward on internal problem-solving, organizational

processes and procedures, reports and deadlines, company politics, and the

administrative demands of their jobs. Consequently the strategic actions they

initiate tend to be inside-out and governed by the company's traditional

approaches, what is acceptable to various internal political coalitions, what is

philosophically comfortable, and what is safe, both organizationally and career

wise. Inside-out strategies, while not disconnected from industry and competitive

conditions, stop short of being market-driven and customer-driven. Rather,

outside considerations end up being compromised to harmonize internal

considerations. The weaker a manager's entrepreneurial instincts and capabilities,

the greater a manager's trend to engage in inside-out strategizing, an outcome that

raises the potential for reduced competitiveness and weakened organizational

commitment to total customer satisfaction.

How boldly managers embrace new strategic opportunities, how much they

emphasize out-innovating the competition, and how often they lead actions to

improve organizational performance are good standard of their entrepreneurial

spirit. Entrepreneurial strategy-makers are inclined to be first-movers,

responding quickly and opportunistically to new developments. They are willing

to take prudent risks and initiate trailblazing strategies. In contrast, reluctant

entrepreneurs are risk-averse; they tend to be late-movers, hopeful about their

chances of soon catching up and alert to how they can avoid whatever 'mistakes'

they believe first-movers have made.

In strategy-making, all managers, not just senior executives, must take prudent

risks and exercise entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship is involved when a district

customer service manager, as part of a company's commitment to better

customer service, crafts a strategy to speed the response time on service calls by

25 percent and commits $15,000 to equip all service trucks with mobile

telephones. Entrepreneurship is involved when a warehousing manager

contributes to a company's strategic emphasis on total quality by figuring out

how to reduce the error frequency on filling customer orders from one error

every 100 orders to one error every 100,000. A sales manager exercises

strategic entrepreneurship by deciding to run a special promotion and cut sales

prices by 5 percent to get market share from rivals. A manufacturing manager

exercises strategic entrepreneurship in deciding, as part of a companywide

emphasis on greater cost competitiveness, to source an important component

from a lower-priced South Korean supplier instead of making it in-house.

Company strategies can't be truly market - and customer-driven unless the

strategy-related activities of managers all across the company have an outside-

oriented entrepreneurial character and contribute to boosting customer

satisfaction and achieving sustainable competitive advantage.

3.2. Why Company Strategies Evolve

Frequent fine-tuning and adjusting of a company's strategy, first in one

department or functional area and then in another, are quite normal. On occasion,

fundamental changes in strategy are called for—when a competitor makes a

dramatic move, when technological breakthroughs occur, or when crisis strikes

and managers are forced to make radical strategy alterations very quickly.

Because strategic moves and new action approaches are ongoing across the

business, an organization's strategy forms over a period of time and then reforms

as the number of changes begins. Current strategy is typically a combination of

previous approaches, fresh actions and reactions, and potential moves in the

planning stage. Except for crisis situations (where many strategic moves are

often made quickly to produce a substantially new strategy almost overnight) and

new company start-ups (where strategy exists mostly in the form of plans and

intended actions), it is common for key elements of a company's strategy to

emerge in bits and pieces as the business develops.

Rarely is a company's strategy so well-conceived and durable that it can withstand

the test of time. Even the best-laid business plans must be adapted to shifting

market conditions, altered customer needs and preferences, the strategic

maneuvering of rival firms, the experience of what is working and what isn't,

emerging opportunities and threats, unforeseen events, and fresh thinking about

how to improve the strategy. This is why strategy-making is a dynamic process

and why a manager must reevaluate strategy regularly, refining and recasting it as

needed.

However, when strategy changes so fast and so fundamentally that the game plan

undergoes major amendment every few months, managers are almost certainly

guilty of poor strategic analysis, bad decision-making, and weak 'strategizing'.

Important changes in strategy are needed occasionally, especially in crisis

situations, but they cannot be made too often without creating organizational

confusion and disrupting performance. Well-crafted strategies normally have a

life of at least several years, requiring only minor adjustment to keep them in

tune with changing circumstances.

3.3. What Does a Company's Strategy Consist Of?

Company strategies concern how: how to grow the business, how to satisfy

customers, how to out-compete rivals, how to respond to changing market

conditions, how to manage each functional piece of the business, how to achieve

strategic and financial objectives. The how of strategy tend to be company-

specific, customized to a company's own situation and performance objectives.

In the business world, companies have a wide degree of strategic freedom. They

can diversify broadly or narrowly, into related or unrelated industries, via

acquisition, joint venture, strategic alliances, or internal start-up. Even when a

company elects to concentrate on a single business, current market conditions

usually offer enough strategy-making room that close competitors can easily

avoid carbon-copy strategies—some pursue low-cost leadership, others stress

various combinations of product/service attributes, and still others elect to cater

to the special needs and preferences of narrow buyer segments. Hence,

descriptions of the content of company strategy necessarily have to be

suggestive rather than definitive.

Figure 1-3 shows the kinds of actions and approaches that reflect a company's

overall strategy. Because many are visible to outside observers, most of a

company's strategy can be deduced from its actions and public pronouncements.

Yet, there's an unrevealed portion of strategy outsiders can only speculate about

the actions and moves company managers are considering. Managers often, for

good reason, choose not to reveal certain elements of their strategy until the

time is right.

To get a better understanding of the content of company strategies, see the

overview of McDonald's strategy in Illustration Capsule 3.

3.4. Strategy and Strategic Plans

Developing a strategic vision and mission, establishing objectives, and deciding

Things 3 2 1 – Elegant Personal Task Management Software

on a strategy are basic direction-setting tasks. They map out where the

organization is headed, its short-range and long-range performance targets, and

the competitive moves and internal action approaches to be used in achieving the

targeted results. Together, they constitute a strategic plan. In some companies,

especially large corporations committed to regular strategy reviews and formal

strategic planning, a document describing the upcoming year's strategic plan is

prepared and circulated to managers and employees (although parts of the plan

may be omitted or expressed in general terms if they are too sensitive to reveal

before they are actually undertaken). In other companies, the strategic plan is not

put in writing for widespread distribution but rather exists in the form of

consensus and commitments among managers about where to head, what to

unimportant ('we don't think it will really affect us') or else study them to death

before taking actions. Being comfortable with the present strategy, they focus

their energy and attention inward on internal problem-solving, organizational

processes and procedures, reports and deadlines, company politics, and the

administrative demands of their jobs. Consequently the strategic actions they

initiate tend to be inside-out and governed by the company's traditional

approaches, what is acceptable to various internal political coalitions, what is

philosophically comfortable, and what is safe, both organizationally and career

wise. Inside-out strategies, while not disconnected from industry and competitive

conditions, stop short of being market-driven and customer-driven. Rather,

outside considerations end up being compromised to harmonize internal

considerations. The weaker a manager's entrepreneurial instincts and capabilities,

the greater a manager's trend to engage in inside-out strategizing, an outcome that

raises the potential for reduced competitiveness and weakened organizational

commitment to total customer satisfaction.

How boldly managers embrace new strategic opportunities, how much they

emphasize out-innovating the competition, and how often they lead actions to

improve organizational performance are good standard of their entrepreneurial

spirit. Entrepreneurial strategy-makers are inclined to be first-movers,

responding quickly and opportunistically to new developments. They are willing

to take prudent risks and initiate trailblazing strategies. In contrast, reluctant

entrepreneurs are risk-averse; they tend to be late-movers, hopeful about their

chances of soon catching up and alert to how they can avoid whatever 'mistakes'

they believe first-movers have made.

In strategy-making, all managers, not just senior executives, must take prudent

risks and exercise entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship is involved when a district

customer service manager, as part of a company's commitment to better

customer service, crafts a strategy to speed the response time on service calls by

25 percent and commits $15,000 to equip all service trucks with mobile

telephones. Entrepreneurship is involved when a warehousing manager

contributes to a company's strategic emphasis on total quality by figuring out

how to reduce the error frequency on filling customer orders from one error

every 100 orders to one error every 100,000. A sales manager exercises

strategic entrepreneurship by deciding to run a special promotion and cut sales

prices by 5 percent to get market share from rivals. A manufacturing manager

exercises strategic entrepreneurship in deciding, as part of a companywide

emphasis on greater cost competitiveness, to source an important component

from a lower-priced South Korean supplier instead of making it in-house.

Company strategies can't be truly market - and customer-driven unless the

strategy-related activities of managers all across the company have an outside-

oriented entrepreneurial character and contribute to boosting customer

satisfaction and achieving sustainable competitive advantage.

3.2. Why Company Strategies Evolve

Frequent fine-tuning and adjusting of a company's strategy, first in one

department or functional area and then in another, are quite normal. On occasion,

fundamental changes in strategy are called for—when a competitor makes a

dramatic move, when technological breakthroughs occur, or when crisis strikes

and managers are forced to make radical strategy alterations very quickly.

Because strategic moves and new action approaches are ongoing across the

business, an organization's strategy forms over a period of time and then reforms

as the number of changes begins. Current strategy is typically a combination of

previous approaches, fresh actions and reactions, and potential moves in the

planning stage. Except for crisis situations (where many strategic moves are

often made quickly to produce a substantially new strategy almost overnight) and

new company start-ups (where strategy exists mostly in the form of plans and

intended actions), it is common for key elements of a company's strategy to

emerge in bits and pieces as the business develops.

Rarely is a company's strategy so well-conceived and durable that it can withstand

the test of time. Even the best-laid business plans must be adapted to shifting

market conditions, altered customer needs and preferences, the strategic

maneuvering of rival firms, the experience of what is working and what isn't,

emerging opportunities and threats, unforeseen events, and fresh thinking about

how to improve the strategy. This is why strategy-making is a dynamic process

and why a manager must reevaluate strategy regularly, refining and recasting it as

needed.

However, when strategy changes so fast and so fundamentally that the game plan

undergoes major amendment every few months, managers are almost certainly

guilty of poor strategic analysis, bad decision-making, and weak 'strategizing'.

Important changes in strategy are needed occasionally, especially in crisis

situations, but they cannot be made too often without creating organizational

confusion and disrupting performance. Well-crafted strategies normally have a

life of at least several years, requiring only minor adjustment to keep them in

tune with changing circumstances.

3.3. What Does a Company's Strategy Consist Of?

Company strategies concern how: how to grow the business, how to satisfy

customers, how to out-compete rivals, how to respond to changing market

conditions, how to manage each functional piece of the business, how to achieve

strategic and financial objectives. The how of strategy tend to be company-

specific, customized to a company's own situation and performance objectives.

In the business world, companies have a wide degree of strategic freedom. They

can diversify broadly or narrowly, into related or unrelated industries, via

acquisition, joint venture, strategic alliances, or internal start-up. Even when a

company elects to concentrate on a single business, current market conditions

usually offer enough strategy-making room that close competitors can easily

avoid carbon-copy strategies—some pursue low-cost leadership, others stress

various combinations of product/service attributes, and still others elect to cater

to the special needs and preferences of narrow buyer segments. Hence,

descriptions of the content of company strategy necessarily have to be

suggestive rather than definitive.

Figure 1-3 shows the kinds of actions and approaches that reflect a company's

overall strategy. Because many are visible to outside observers, most of a

company's strategy can be deduced from its actions and public pronouncements.

Yet, there's an unrevealed portion of strategy outsiders can only speculate about

the actions and moves company managers are considering. Managers often, for

good reason, choose not to reveal certain elements of their strategy until the

time is right.

To get a better understanding of the content of company strategies, see the

overview of McDonald's strategy in Illustration Capsule 3.

3.4. Strategy and Strategic Plans

Developing a strategic vision and mission, establishing objectives, and deciding

Things 3 2 1 – Elegant Personal Task Management Software

on a strategy are basic direction-setting tasks. They map out where the

organization is headed, its short-range and long-range performance targets, and

the competitive moves and internal action approaches to be used in achieving the

targeted results. Together, they constitute a strategic plan. In some companies,

especially large corporations committed to regular strategy reviews and formal

strategic planning, a document describing the upcoming year's strategic plan is

prepared and circulated to managers and employees (although parts of the plan

may be omitted or expressed in general terms if they are too sensitive to reveal

before they are actually undertaken). In other companies, the strategic plan is not

put in writing for widespread distribution but rather exists in the form of

consensus and commitments among managers about where to head, what to

accomplish, and how to proceed. Organizational objectives are the part of the

strategic plan most often spelled out explicitly and communicated to managers

and employees.

However, annual strategic plans seldom anticipate all the strategically relevant

events that will transpire in the next 12 months. Unforeseen events, unexpected Wondershare uniconverter 11 6 4 6 0.

opportunities or threats, plus the constant emerging of new proposals encourage

managers to modify planned actions and make 'unplanned' reactions. Postponing

the redrafting of strategy until it's time to work on next year's strategic plan is

both foolish and unnecessary. Managers who confine their strategizing to the

company's regularly scheduled planning cycle (when they can't avoid turning

something in) have a wrongheaded concept of what their strategy-making

responsibilities are. Once-a-year strategizing under 'have to' conditions is not a

prescription for managerial success.

4. Strategy Implementation and Execution

The strategy-implementing function consists of seeing what it will take to make

the strategy work and to reach the targeted performance on schedule — the skill

here is being good at figuring out what must be done to put the strategy on

schedule, execute it excellently, and produce good results. The job of

implementing strategy is mainly a practice, close to-the-scene administrative

task that includes the following principal aspects:

1.Building an organization capable of carrying out the strategy

successfully.

2.Developing budgets that steer resources into those internal activities

critical to strategic success.

3.Establishing strategy-supportive policies.

4.Motivating people in ways that stimulate them to pursue the target

objectives energetically and, if need be, modifying their duties and job

behavior to better fit the requirements of successful strategy execution.

5.Tying the reward structure to the achievement of targeted results.

6.Creating a company culture and work climate useful for successful

strategy implementation.

7.Installing internal support systems that enable company personnel to

carry out their strategic roles effectively day in and day out.

8.Performing best practices and programs for continuous improvement.

9.Applying the internal leadership needed to drive implementation

forward and to keep improving on how the strategy is being executed.

The administrative aim is to create 'fits' between the way things are done and

what it takes for effective strategy execution. The stronger the fits, the better the

execution of strategy. The most important fits are between strategy and

organizational capabilities, between strategy and the reward structure, between

strategy and internal support systems, and between strategy and the organization's

culture (the latter emerges from the values and beliefs shared by organizational

members, the company's approach to people management, and rooted behaviors,

work practices, and ways of thinking). Fitting the ways the organization does

things internally to what it takes for effective strategy execution helps unite the

organization behind the accomplishment of strategy.

The strategy-implementing task is easily the most complicated and time-

consuming part of strategic management. It cuts across virtually all facets of

managing and must be initiated from many points inside the organization. The

strategy implementer's agenda for action emerges from careful assessment of

what the organization must do differently and better to carry out the strategic

plan proficiently. Each manager has to think through the answer to 'What has to

be done in my area to carry out my piece of the strategic plan, and how can I best

get it done?' How much internal change is needed to put the strategy into effect

depends on the degree of strategic change, how much internal practices are on

the wrong track from what the strategy requires, and how well strategy and

organizational culture already match. As needed changes and actions are

identified, management must supervise all the details of implementation and

apply enough pressure on the organization to convert objectives into results.

Depending on the amount of internal change involved, full implementation can

take several months to several years.

5. Evaluating Performance, Reviewing New Developments,

and Initiating Corrective Adjustments

None of the previous four tasks are one-time exercises. New circumstances call

for corrective adjustments. Long-term direction may need to be altered, the

business redefined, and management's vision of the organization's future course

narrowed or broadened. Performance targets may need raising or lowering in

light of past experience and future prospects. Strategy may need to be modified

because of shifts in long-term direction, because new objectives have been set,

or because of changing conditions in the environment.

The search for ever better strategy execution is also continuous. Sometimes an

aspect of implementation does not go as well as intended and changes have to be

made. Progress is typically uneven—faster in some areas and slower in others.

Some tasks get done easily; others prove difficult. Implementation has to be

thought of as a process, not an event. It occurs through the gross effects of many

Things 3 2 1 – Elegant Personal Task Management System

managerial decisions and many actions on the part of work groups and individuals

Things 3 2 1 – Elegant Personal Task Management Tool

across the organization. Budget revisions, policy changes, reorganization,

personnel changes, reengineered activities and work processes, culture—

changing actions, and revised compensation practices are typical actions

managers take to make a strategy work better.

[ PREV ] [NEXT ]

[TABLE OF CONTENTS ]

[PART I ] [PART II ] [PART III ]